The Old Spanish Trail

When we think of the westward expansion of the United States most of us picture Lewis and Clark heading off from Camp Wood to map the newly acquired territory of the Louisiana Purchase and pushing on to the Pacific Ocean. Or we might envision families like that of Laura Ingalls Wilder trundling across the wide-open prairie in covered wagons. But when it comes to the Southwest it seems that in the popular consciousness it springs to life fully formed sometime in the 1850s, complete with a sassy barmaid, weather-worn false front architecture, a network of trains and stagecoaches, and most importantly of all desperate horse thieves, bandits and a heroic sheriff that always gets his man. But the truth of westward expansion through the Southwest is no less fascinating, perilous, or historically significant than the more northern expansion routes and it doesn’t fail to provide its share of brave adventurers, nefarious outlaws, and charming tales along the way.

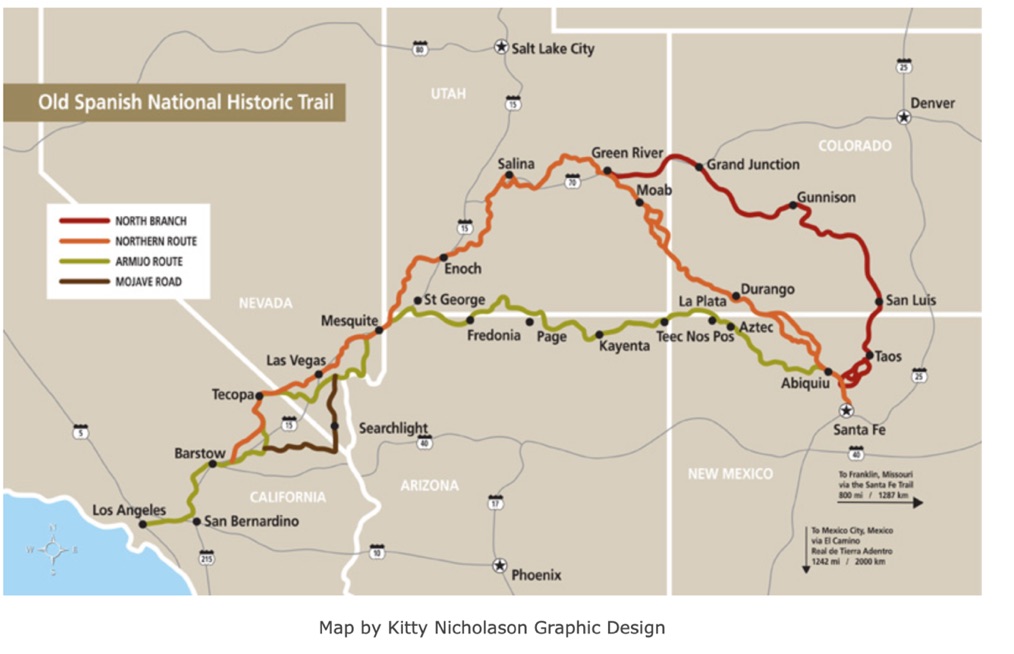

When the Spanish arrived in the 16th century there was already a network of footpaths created by the indigenous people webbing what is now South West Colorado, North West New Mexico, Southern Utah, Northern Arizona, the bottom tip of Nevada passing through modern-day Las Vegas, and Southern California. The paths were dangerous, sprawling, and unmapped. Santa Fe, New Mexico was an established city by the Spanish Period of 1776 and Spanish Priests were setting off to explore the surrounding territory making it as far west as Utah. Simultaneously the Spanish were beginning to settle in Southern California. It wasn’t until 53 years later in 1829 when the need for a direct trade route between New Mexico and Los Angeles pushed Mexican trader Antonio Armijo to lead the first commercial caravan from Abiquiú, New Mexico to Los Angeles. The path he chose used a combination of those original footpaths, routes discovered by the Spanish priests, and mule paths. Over the next 15 years, his 2,700-mile path spanning mountains, deserts, rivers, and through California’s coastal valleys was used to carry woolen goods made in Santa Fe to Los Angeles which were traded for horses and mules. The route was officially mapped for the United States by John C. Frémont and his guide Kit Carson and named The Old Spanish Trail. This trade route is often cited as one of the most arduous in United States history and is made up of 4 interconnected portions. The trek was made annually, leaving Santa Fe in November with 20-200 men and nearly twice as many mules loaded down with goods to trade and arriving in California in early February. With 3 months to perform their trading, they would head east again in April hoping they were not too late to still find water in the desert and the rivers would still be low enough to cross. If the trade was successful, they would be making their return with several hundred horses and mules. The travelers on the trail could be just as treacherous as the trail itself, used by horse raiders who could steal hundreds to thousands of horses in a single raid, slave traders trafficking captured women and children to sell to Mexican ranchers, and warfare between the indigenous groups made passage a dangerous undertaking.

Though the Old Spanish Trail(OST) was difficult and perilous the benefits could not be ignored. It gave landlocked New Mexico access to the ports of Los Angeles, cemented Los Angeles as a center for trade, and provided a small but significant stream of immigrants westward into California. The journey along the Old Spanish trail made by the families of Juan Felipe Peña and Juan Manuel Cabeza Vaca is one of the most endearing tales of immigration along this route. The two men were granted land by Governor Manuel Micheltorena that encompassed all of Lagoon Valley, they set out with their families to make the two-month journey along the trail, with the youngest daughter of each family nestled into the side saddle of a “gentle mule” they went west and made a new home for themselves, Juan Manuel Cabeza Vaca becoming the eventual namesake of modern Vacaville, California.

As freight wagons came into use, new paths that would be easier for them to pass developed. Eventually, The Old Spanish Trail was abandoned. Portions of the trail have been preserved. In 2001 the portions of the trail that runs across Nevada between Arizona and California were placed on the National Register of Historic Places and in 2002 the Old Spanish Trail was named the fifteenth National Historic Trail recognized by the United States.